http://www.artpractical.com/column/endurance-tests-black-is-the-subject/

Black is the Subject: Dana Michel is Moving

By Anna Martine WhiteheadApril 14, 2016

“Endurance Tests” is an irregular column on current explorations of representation, the ethereal, and compulsiveness by black artists working in the field of performance. Across profiles and interviews, the column takes seriously the proposition of performance as a repeatable and assimilable text. “Endurance Tests” will examine contemporary performance-makers actively syncretizing the many implications of "blackness": illegality, contagion, maladaptivity, and a privileged relationship to cool.

Montreal-based choreographer Dana Michel has requested a bit more time; our interview was postponed twice since our morning appointment. This is no problem for me. Since seeing her 75-minute deliberation on performance and spectatorship at Chicago’s On Edgefestival, I’ve been angsty as a teenage inamorata to speak with the choreographer of Yellow Towel (named a “Top Ten” dance moment in Dance Current and Time Out New York, and “engrossing” by the New York Times). Michel wants 3 p.m.? Works for me.

Yellow Towel—which positions Michel’s mumbling, munching, and contorting body within a minimalist white space—originates from her childhood practice of placing a yellow towel atop her head to attain “long, silky” locks. Rather than a narrative of abnegation and overcoming of internalized racism, however, Yellow Towel is an offering to a public that rarely gets to see the wealth of a Black body behaving so badly. Michel moves through the space performing a seemingly disjointed oeuvre of ungraceful and almost clumsy actions. There is a general sense of shiftiness in her energy, a lack of dependability that thrives alongside an absolute clarity of movement.

Yellow Towel gifts us an alternative and orders us to watch

Consumers of Black culture (read: humans) are inundated with archetypes of the Black body: the heroic Black body, the graphically dead Black body, the righteously raging or mourning Black body. Yet it is our true bodies in all their regularity—our dysphoric, ambiguous, music-loving-but-unable-to-keep-a-beat regular-ass bodies—that we are led to believe aren’t worthy of anyone’s gaze, least of all our own. With Yellow Towel, Michel gifts us an alternative and orders us to watch.

In her review of Yellow Towel for On the Boards, African American performer Shontina Vernon writes, “I mostly was left with the question of why I needed to be present for this art to happen.”1 This guarded, curious frustration exists for good reason: Black performers have struggled to make the virtuosic Black body legible as such. As I write this, George Wolfe and Savion Glover—Glover, a czar of superlative blackness—are busy on Broadway restaging Shuffle Along, the first widely successful all-Black musical, with a few updates: At its 1921 premiere, Shuffle Along performers had to wear blackface. Since the days of obligatory dancing on the poop deck, Black performers have understood the stakes. There is a sense in all of us that we did not come this far to fail, not when we still have so much further to go.

It is an unnamed but burning desire to only see ourselves jump higher and land softer that often precludes us from bearing witness to our tumble and fall, equally glorious though they may be. So the revelation of a regularly mad Black woman becomes personal. Ultimately, Michel has created a piece that is deeply intimate to the point of unintelligibility to those who aren’t in the know, making the work powerful in the way that confidences can be, and, at times, just as disturbing, confusing, and frustrating as a secret between sisters. I asked Michel about the implications of such an intimate portrayal for such a diverse audience.2

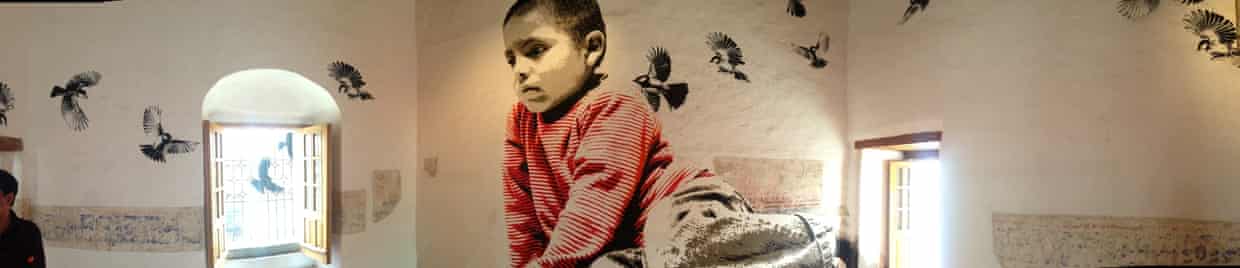

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Ian Douglas.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Ian Douglas.

Dana Michel: I set up a situation that is my ideal. I appreciate having space to just look at all of someone and watch them do what they’re doing without any kind of contract to engage in any particular way. I feel such a freedom when I don’t have to worry about the moment when I’m going to try to connect with you, a stranger, through the lights and the hundreds of other people in the room. The beginning of making this work was quite shaped by my experiences as an audience member. As an audience member, I appreciate [having] a lot of space and I appreciate [falling] asleep in a performance, to go off to some other place and come back.

Also, thinking about Caribbean culture, or dancehall, for instance. When you’re in the club and you’re in the moves, the gaze is down here [Michele indicates interiority with low-lidded eyes]. The gaze is on the ground because you’re so connected to what’s going on in here [indicating her body and limbs] that you’re talking to whoever you need to talk to through your body, through the top of your head, the fucking smell of your sweat is talking to someone. It’s super powerful. I always find that when I watch dancehall or other social forms of dance that could be called “dirty dance” trying to be transformed onto the stage—all of a sudden we add this layer of looking. It destroys the nature of the beast in some way.

Anna Martine Whitehead: What do you make of the Chicago audience member’s critique, when she expressed her unease at witnessing what she interpreted as psychosis laid bare for an audience that included more white people than any other race? I read it as a discomfort with seeing Yellow Towel outside of a Black-only space—a safe space—and amongst white audiences.

DM:

Certainly the kind of feedback that’s been happening in the States is different than anything that’s come up in the past. Maybe some things that were in the air are the things that are the most prominent here.

I guess I’d heard it. But that feeling hadn’t completely rooted until you just said it, so now I’m just processing it. I’m thinking about a piece I saw at American Realness in January, and I was maybe one of two Black people in the room. It was [Jaamil Olawale Kosoko’s] #negrophobia, and it was digging, digging, digging. And I felt super uncomfortable as one of the only Black people in the room. I’ve had that feeling maybe one other time. In that particular performance I felt like, “Why is everybody looking at me? Are they looking at me to see what my reaction is? Are they looking at me to see if it’s okay for them to feel the way that they feel?” I felt like there was a big spotlight on me because I was the Black woman sitting in the room and Black is the subject on stage. It was crazy uncomfortable.

Before this tour, there have been one to two Black people or people of color in the audience, tops. As someone who has grown up in environments where I’m one of only two or three, I’m now realizing how much that has meant that I’ve become extremely good at effacing. There’s a blending that happens. Even though you’re the only person who looks the way you look in the room, you’re trying to make it such that no one can see that.

This is part of the Utopia that I created for myself. I’m just going to put my hands deep in the guts of all the things I never allowed myself to touch. That’s the permission that I gave myself. At a certain point I was slapped in the face with the fact that I didn’t know what I was suppressing. Or I knew but I didn’t realize how much it was affecting me or how much it was affecting the shape of my life or the choices that I make.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Ian Douglas.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Ian Douglas.

AMW:

Do you feel that you are making this work for Black audiences?

DM:

In the past it felt more like a general sharing. But performing in the States in the past month, it is the first time that I’ve seen so much variation in audience. I’ve been crying all month long during my bow. It’s been completely overwhelming. At the end of the show, when I finally look up and I see all of the diverse shades and shapes, it’s beautiful. It’s like you don’t even realize that that was missing because you’re so used to not seeing it. The possibility that there are different groups of people in the room who can relate to the work in a very different way or from a different angle than it has been in the past… I didn’t think it was possible—it wasn’t even a consideration. Then all of a sudden it is like being in a room performing with my family. It’s brought a whole new level of vulnerability.

AMW:

Talk about your practice. Yellow Towel is the longest solo you’ve made to date.

DM:

I used to have a very dogmatic stance of not making anything more than 5–10 minutes long—because I felt that I didn’t have anything else to say. As though everything over ten minutes long was masturbation and I refused.

I’m slow, and I accept that now. Just the other day I was pouring over [experimental theater group] Forced Entertainment’s website, and I was looking at [founder] Tim Etchells’ CV and his output. How do these people do it? He’s been popping out a piece every year since 1984.

I look at output like that and think, “This is impossible.” I’m always way too slow. I’m always the last one at the dinner table. So when I have to talk about “my body of work,” it’s like there’s suddenly a very big ocean and I have to go do a bit of scuba diving. “Oh yes, there’s this shell in 2005. I did this shell in the context of that cold current over there…” For a long time part of me didn’t understand people who say, “We’re all about the process and we don’t care about the outcome”—when I look at what I’ve been doing for the last ten years, this is actually where I place all kinds of premiums: process.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Maya Fuhr.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Maya Fuhr.

AMW:

Is your relationship to time at all to do with motherhood?

DM:

I got pregnant at the same time I started to make Yellow Towel. I was seven months into the process of creating Yellow Towel when I found out I was pregnant. Having [my son] gave me more permission to sit in the relationship to time than I already had. It’s been a lifelong struggle that I’ve been tapped on the wrist for—my relationship to time. There’s the typical classic Colored People’s Time…

AMW:

And your family is from St. Lucia, so that’s double CPT.

AMW:

And what you’re working on now—is it also a slowly developing process?

DM:

It’s a continuation of Yellow Towel. It’s like I went trick-or-treating, and I came home with these huge bags and bags of Halloween candy. I didn’t even know all of this candy existed! Now I’ve taken the bags and I’ve emptied them out and I have to sort through it. That’s where I’m at. Maximalist sloth garbage. Sifting through the debris.

When I spoke about Yellow Towel before, I would first frame it as a piece about my hair. And then it became “My Black Piece,” the piece that I make where I actually get to look at the fact that I’m Black and what’s going on there. There was some kind of clear new paragraph in making Yellow Towel [from other work]. This [new work] doesn’t feel like a new paragraph—just a continuation of the last paragraph.

I was in France with my partner’s family. His cousin is an anthropologist, and she was showing us home videos of bonobos. We’re sitting in the living room and I’m the only Black person in the room. … It became something that was very fucking uncomfortable. This was a moment where I was like, “Ah, yes, I’ve just started to scratch a surface with Yellow Towel. There’s more to scratch at.”

I was speaking with the cousin and feeling… kind of weird. Similar to this woman you mentioned who felt weird to be in the audience with white people and watching [me] let this all out. I felt, also, “I’m the only Black person in the room with these monkeys. Are they looking at me and making comparisons?” I spoke with the anthropologist cousin, and she said, “Ah, you’re experiencing Freud’s uncanny thing.” Yes, for sure, but there’s also the other thing that I feel like I can’t really talk to you about. I went for a walk in the countryside, and new thoughts of the new work began to formulate.

AMW:

It’s a very intuitive process with you, it seems, which works cerebrally as much as deep in your gut.

DM:

I still feel—and maybe will feel for the rest of my life—like an outsider, a newcomer. Art came to me so late in the development of myself as a human. I was 25 the first time I really started looking at art and performance. It was not a part of how I was raised, or what any of my friends were into, or my schooling.

I was in business school and started dating someone, and he brought me to my first rave. It cracked open a new space—it was like, “Oh, there’s another place! I thought I had to become an accountant!” There’s been similar micro-moments over the years. Happening upon an Aphex Twin video and thinking, “What is that?” A friend of mine had free tickets to a contemporary dance show, and I went to see this company from Montreal. I didn’t know what I was looking at or what was going on, but I loved this experience of sitting by myself in this theater not knowing what the fuck was going on. It was a wonderful feeling.

I think it stems from my relationship to time and how long it takes me to eat a crumb. It’s been fifteen years and I still feel really very naïve. I digest slowly, but all the nutrients are there.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Maxyme G. Delisle.

Dana Michel. Yellow Towel (performance still); 75:00. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Maxyme G. Delisle.

AMW:

When did you begin your formal training?

DM:

I was at my job one day and saw an ad in a newspaper for a contemporary dance [degree]. I called [the university] randomly. The director said, “Yes, come for an audition!” A year later I auditioned, and not long after that I was going to dance school. I was out of school for six years before I did danceWEB.3

Eventually I had a nervous breakdown trying to be a “normal” person. I was working in a hospital job for ten years and I vowed I’d never leave it because it was so practical and it allowed me to keep a foot in the “real” world. I took a leave of absence and a friend said, “Since you’re taking a year off, why don’t you apply for this danceWEB thing?” Which, to me, was for intense professional people and I had no business doing that kind of thing.4

AMW:

And now? How does it feel now to have no feet left in that “real” world?

DM:

It’s a constant adjustment. It’s changing week by week and day by day. It’s a huge process to have been raised a certain way and having that shape your thinking, and then to be making up all kinds of new rules and digging the road as you’re trying to walk in it. You’re not quite sure you have the right. And then also, I have a child who’s fresh on the scene.

Very recently, I have been feeling: “That’s enough of saying, ‘Thank you very much, this is going very well right now, I don’t know how much longer this is going to last, maybe next year this will be over.’” The constant I-don’t-know-what’s-happening. I’m trying to let myself be fully in this situation. Whatever way things need to evolve, they will, and I don’t need the intense guilt around things going quite well.

Last week I was in a hotel, up until six in the morning, writing and thinking about things that I wanted to do or dig into. I often think, “Well, this is it, I have nothing else to say, so I’m not going to last much longer. The jig is up and people are going to know any day now. I’m a one-hit-wonder.” But maybe it’s okay to think about what else I might want to do. It feels crazy. It’s a crazy, beautiful, amazing gift to spend all my time doing this thing. Having wonderful conversations that are helping me to evolve and sweat a little.

I am quite lucky. I have people who love me and want to support me. So rather than wasting a bunch of energy and guilt, maybe I can just reinvest that energy into the opportunity that’s being given to me.

________

This article is made possible through our Writers Fund, thanks to readers like you. Help us keep it going!